Bill Viola

Bill Viola | |

|---|---|

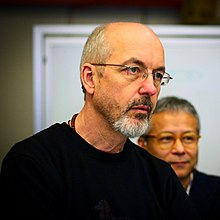

Viola in 2009 | |

| Born | January 25, 1951 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | July 12, 2024 (aged 73) Long Beach, California, U.S. |

| Education | Syracuse University (BFA) |

| Known for | Video art Electronic art New media art |

| Notable work | Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House (1982) |

| Website | billviola |

William John Viola Jr. (US: /ˈvaɪoʊlə/ VY-oh-lə, UK: /ˈviːoʊlə/ VEE-oh-lə; January 25, 1951 – July 12, 2024) was an American video artist[1] whose artistic expression depended upon electronic, sound, and image technology in new media.[2] His works focus on the ideas behind fundamental human experiences such as birth, death, and aspects of consciousness.[3]

Early life and education[edit]

William John Viola Jr. was born on January 25, 1951, in Flushing, Queens, New York,[4] and grew up in Queens and Westbury. He attended P.S. 20, in Flushing, where he was captain of the TV Squad. On vacation in the mountains with his family, he nearly drowned in a lake, an experience he described as "… the most beautiful world I've ever seen in my life" and "without fear," and "peaceful."[5]

In 1973, Viola graduated from Syracuse University with a Bachelor in Fine Arts in experimental studies.[6] He studied in the College of Visual and Performing Arts, including the Synapse experimental program, which evolved into CitrusTV.[7]

Career[edit]

From 1973 to 1980, Viola studied and performed with composer David Tudor in the new music group "Rainforest" (later named "Composers Inside Electronics"[8]). From 1974 to 1976, Viola worked as technical director at Art/tapes/22, a pioneering video studio led by Maria Gloria Conti Bicocchi, in Florence, Italy where he encountered video artists Nam June Paik, Bruce Nauman, and Vito Acconci. From 1976 to 1983, he was artist-in-residence at WNET Thirteen Television Laboratory in New York. In 1976 and 1977, he travelled to the Solomon Islands, Java, and Indonesia to record traditional performing arts.[9]

Viola was invited to show work at La Trobe University (Melbourne, Australia) in 1977, by cultural arts director Kira Perov. Viola and Perov later married, beginning an important lifelong collaboration in working and traveling together. In 1980, they lived in Japan for a year and a half on a Japan/U.S. cultural exchange fellowship where they studied Buddhism with Zen Master Daien Tanaka. During this time, Viola was also an artist-in-residence at Sony Corporation's Atsugi Laboratories.[10]

In 1983, he became an instructor in Advanced Video at the California Institute of the Arts, in Valencia, California. Viola received a Guggenheim Fellowship[11] for fine arts in 1985. He represented the United States at the 46th Venice Biennale in 1995 for which he produced a series of works called Buried Secrets, including one of his best known works The Greeting, a contemporary interpretation of Pontormo's The Visitation. In 1997, the Whitney Museum of American Art organized and toured internationally a major 25-year retrospective of Viola's work.[9]

Viola was the 1998, Getty Scholar-in-residence at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Later, in 2000, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2002, he completed Going Forth By Day, a digital "fresco" cycle in high-definition video, commissioned by the Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin and the Guggenheim Museum, New York.[12]

In 2003,The Passions was exhibited in Los Angeles, London, Madrid, and Canberra. This was a major collection of Viola's emotionally charged, slow-motion works inspired by traditions within Renaissance devotional painting.[13]

The first biography of Viola, entitled Viola on Vídeo, was written by Federico Utrera (King Juan Carlos University) and published in Spain in 2011.[14]

Bill Viola studio[edit]

Bill Viola studio is run by his wife, Kira Perov, who is the executive director. She worked with Viola from 1978 managing and assisting him with his videotapes and installations. She documents their work in progress on location. All publications from the studio are edited by Perov.[15]

Death[edit]

Viola died from complications of Alzheimer's disease at home in Long Beach, California, on July 12, 2024, at the age of 73, leaving behind his wife and longtime creative collaborator, Kira Perov, sons Blake and Andrei Viola, and daughter-in-law Aileen Milliman.[16][4][17]

Artwork[edit]

Style[edit]

Viola's art deals largely with the central themes of human consciousness and experience – birth, death, love, emotion, and a kind of humanist spirituality. Throughout his career he drew meaning and inspiration from his deep interest in mystical traditions, especially Zen Buddhism, Christian mysticism, and Islamic Sufism, often evident in the transcendental quality of some of his works.[18] Equally, the subject matter and manner of western medieval and renaissance devotional art informed his aesthetic.

He often explored dualism, or the idea that comprehension of a subject is impossible unless its opposite is known. For example, a lot of his work has themes such as life and death, light and dark, fire and water, stressed and calm, or loud and quiet.[19]

His work can be divided into three types, conceptual, visual, and a unique combination of the two. Gardner feels that Viola's visual work, such as "The Veiling", and his combination of both the conceptual and visual, such as "The Crossing," are impressive and memorable.[20]

Viola's work often exhibits a painterly quality, with his use of ultra-slow motion video encouraging the viewer to sink into the image and connect deeply to the meanings contained within it. This quality makes his work perhaps unusually accessible within a contemporary art context. As a consequence, his work often receives mixed reviews from critics, some of whom have noted a tendency toward grandiosity and obviousness in some of his work.[21]

Viola's interest in capturing the essence of emotion through recording of its extreme display began at least as early as his 1976 work, The Space Between the Teeth, a video of himself screaming, and continued with such works as the 45-second Silent Mountain (2001), which shows two actors in states of anguish, which Viola described as “probably the loudest scream I’ve recorded.”[22]

If Viola's depictions of emotional states with no objective correlative — emotional states for which the viewer has no external object or event to understand them by—are one feature of many of his works, another, which has come to the forefront, is his reference to medieval and classical depictions of emotion. His subdued Catherine's Room 2001, has many scene by scene parallels with Andrea di Bartolo's 1393 St. Catherine of Siena Praying.[23]

Viola's work has received critical accolades. Critic Marjorie Perloff singles him out for praise. Writing at length about the necessity of poetic works responding to and taking advantage of contemporary computer technologies, Perloff sees Viola as an example of how new technology—in his case, the video camera—can create entirely new aesthetic criteria and possibilities that did not exist in previous incarnations of the genre — in this case, theater.[24]

Video art projects[edit]

.jpg/220px-Bill_and_Jamie_(3342782140).jpg)

While many video artists have been quick to adopt new technologies to their medium, Viola relied little on digital editing. Perhaps the most technically challenging part of his work, and that which has benefited most from the advances since his earliest pieces, is his use of extreme slow motion.[25]

Reverse Television[edit]

Reverse Television (1983) is a 15-minute montage of people watching video cameras as though they were televisions.[26]

The Quintet Series[edit]

The Quintet Series (2000-2001) is a set of four separate videos that shows the unfolding expressions of five actors in slow motion so that details of their changing expressions can be detected. The work references European Renaissance Old Masters such as Hieronymous Bosch and Dieric Bouts[27]

Collaboration with Nine Inch Nails[edit]

In 2000, Viola collaborated with the industrial rock band Nine Inch Nails and its lead singer Trent Reznor to create a video suite for the band's tour. The triptych mainly is focused on water imagery and was supposed to be integral with the songs that were played.[28]

An Ocean Without a Shore[edit]

In 2007, Viola was invited back to the 52nd Venice Biennale to present an installation called "Ocean without a Shore", which was named after a quote from Ibn ʿArabī.[29] The work consists of people standing in the foreground with nothing but black behind them. Each of them seem to produce gallons of water from themselves as if they were waterfalls. The water comes gushing out of their bodies as if they are being reborn. This main piece seems to creates the effect of appearing as a nearly transparent wall of glass. Viola described the piece in an interview as being "about the fragility of life, like the borderline between life and death is actually not a hard wall; it’s not to be opened with a lock and key, it's actually very fragile, very tenuous."[30]

Observance[edit]

Observance (2002), is a work which may be taken partly as a response to the September 11 attacks.[31] The installation involves about four or five individuals in a small frame. Although cramped in this small space, they seem to not want to move out of it. One of the youngest individuals in the group comes forward to the front center of the crowd looking at something with an air of solace. In this action, the actions of the other individuals makes more sense. There is something foreboding and tragic in front of them.

The Tristan Project[edit]

In 2004, Viola embarked on The Tristan Project. At the invitation of opera director Peter Sellars, he created video sequences to be shown as a backdrop to the action on stage during the performance of Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde. Using his extreme slow motion, Viola's pieces used actors to portray the metaphorical story behind Wagner's story, seeing for example the first act as an extended ritual of purification in which the characters disrobe and wash themselves before finally plunging headlong into water together (in Wagner's story, the two characters maintain the facade of being indifferent to each other (necessary because Isolde is betrothed to Tristan's uncle) before, mistakenly believing they are going to die anyway, and reveal their true feelings). The piece was first performed in Los Angeles at Disney Hall on 3 separate evenings in 2004, one act at a time, then given complete performances at the Bastille Opera in Paris in April and in November 2005.[32] The video pieces were later shown in London without Wagner's music in June to September 2006, at the Haunch of Venison Gallery and St. Olave's School, London. The Tristan project returned, both in music and video, to the Disney Hall in Los Angeles in April 2007, with further performances at New York City's Lincoln Center in May 2007 and at the Gergiev Festival in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in September 2007.[33]

The Night Journey[edit]

In 2005, he began working with Tracy Fullerton and the Game Innovation Lab at USC on the art game, The Night Journey, a project based on the universal story of an individual's mystic journey toward enlightenment.[34] The game has presented at a number of exhibits worldwide as a work in progress.[35] It was awarded Sublime Experience at IndieCade 2008.[36]

Bodies of Light[edit]

In October 2009, Viola's solo exhibition entitled "Bodies of Light" appeared at the James Cohan Gallery in New York. Featured in the exhibition was Pneuma (1994), a projection of alternating images evoking the concept of fleeting memories. Also on view were several pieces from the Viola's ongoing "Transfiguration" series, which he evolved from his 2007 installation Ocean Without a Shore.[37]

Other projects[edit]

In 2004, Viola began work on a new production of Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde, a collaboration with director Peter Sellars, conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen, and executive producer Kira Perov. The opera premiered at the Opéra National de Paris in 2005 and Viola's video work was subsequently shown as LOVE/DEATH The Tristan Project at the Haunch of Venison Gallery and St Olave's School, London, in 2006 and at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles in 2007. [33]. During 2007, the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Sevilla, organized an exhibition at the Palace of Charles V in la Alhambra- Granada- in which Viola's work dialogues with the Fine Arts Collection of the museum.[38]

Viola's Three Structures[edit]

Viola felt as if there are three different structures to describe patterns of data structures. There is the branching structure, matrix structure, and schizo structure.[39]

"The most common structure is called branching. In this structure, the viewer proceeds from the top to bottom in time."[40] The branching structure of presenting data is the typical narrative and linear structure. The viewer proceeds from a set point A to point B by taking an exact path, the same path any other reader would take. An example of this is Google because users go into this website with a certain mindset of what they want to search for, and they get a certain result as they branch off and end at another website.

The second structure is the Matrix structure. This structure describes media when it follows nonlinear progression through information. The viewer could enter at any point, move in any direction, at any speed, pop in and out at any place.[40] Like the branching structure, this also has its set perimeters. However, the exact path that is followed is up to the user. The user has the option of participating in decision-making that affect the viewing experience of the media. An example of this is Public Secrets, a website that reveals secrets of the justice and the incarceration system within the U.S. for women. There is a set boundary of what users can and cannot do while presenting them with different themes and subjects users are able to view. Different users will find themselves taking different paths, using flash cues to guide themselves through the website. This vast selection of paths presents many users with a unique viewing experience (in relation to that of the previous persons). As well, they have the choice to read the excerpts from these women or hear it out loud. This connects to Borges' "The Garden of Forking Paths"[41] where the participant has a variety of choices on how they see a story unfold before them. Each time, they can create a different path.

The last structure is called the schizo, or the spaghetti model. This form of data structure pertains to pure or mostly randomness. "Everything is irrelevant and significant at the same time. Viewers may become lost in this structure and never find their way out."[40]

Awards[edit]

Viola was awarded the XXIst Catalonia International Prize in 2009. The Premi Internacional Catalunya was created by the autonomous government of Catalonia, the Generalitat de Catalunya, to be awarded to those who make notable contributions to the advancement of human, cultural, and scientific values.[42] The award honors an individual "whose creative work has made a significant contribution to the development of cultural, scientific or human values anywhere in the world".

- 1984 Polaroid Video Art Award for outstanding achievement, US[9]

- 1985 Guggenheim Fellowship for Fine Arts, US[43]

- 1987 Maya Deren Award, American Film Institute, US[44]

- 1989 John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Award, US[9]

- 1993 Skowhegan Medal (Video Installation), US[45]

- 1993 Medienkunstpreis, Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Karlsruhe, and Siemens Kulturprogramm, Germany[9]

- 2000 Elected member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences[46]

- 2003 Cultural Leadership Award, American Federal of Arts, US[9]

- 2006 NORD/LB Art Prize, Bremen, Germany[9]

- 2006 Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, government of France[9]

- 2009 Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts, MIT, Cambridge, MA[47] He was awarded $75,000 and was able to go to MIT and help enhance the creative groups there.

- 2009 Catalonia International Prize, Barcelona, Spain[3]

- 2010 Honorary doctorate from the University of Liège,[48] Belgium

- 2011 Praemium Imperiale, Japan[49]

- 2017 Elected as an Honorary Royal Academician by the Royal Academy of Arts, UK [9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ [1] Viola, Bill bio at the Getty Archive

- ^ Ross, David A. Forward. "A Feeling For the Things Themselves". Bill Viola Paris, Flammarion with Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

- ^ a b "Biography". www.billviola.com.

- ^ a b "Bill Viola, Celebrated Video Artist Who Played With Time, Dies at 73". The New York Times. July 13, 2024. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Bill Viola: The Eye of the Heart. Dir. Mark Kidal. DVD. Film for the Humanities & Sciences, 2005.

- ^ Arya, Rina (2003). "Viola, Bill [ William ]". Viola, Bill. Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T096533.

- ^ "Bill Viola | Biography | The Cohen Family Collection". jmcohen.com. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "cie home". composers-inside-electronics.net.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Bill Viola Hon RA (b. 1951), Royal Academy of Arts, London".

- ^ [2] Viola, Bill at MoMA

- ^ "Bill Viola - John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation". www.gf.org. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

- ^ "Bill Viola Going Forth By Day". Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "Bill Viola: The Passions (Getty Exhibitions)". www.getty.edu. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Press, Europa (June 20, 2011). "Llega 'Viola on Vídeo', de Federico Utrera". www.europapress.es. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ "Interview With Kira Perov From Bill Viola Studio ⇠ Blog ⇠ Borusan Contemporary". www.borusancontemporary.com. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Muere Bill Viola, 'el Caravaggio del videoarte'". La Vanguardia. July 13, 2024. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ "Ci lascia Bill Viola, padre e maestro indiscusso della videoarte". www.exibart.com (in Italian). Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "Bill Viola | American Academy of Arts and Sciences". www.amacad.org. June 6, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Quaranta, Dario (January 25, 2019). "Bill Viola | Video art". Dada Blob... Exotic worlds and Pop culture! (in Italian). Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ James Gardner: Is it art?[permanent dead link], The National Review, May 4, 1998 [dead link]

- ^ "Bill Viola A Retrospective". artreview.com. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Silent Mountain". TBA 21 Gallery. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "Bill Viola Catherine's Room". National Gallery of Scotland. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Marjorie Perloff: The Morphology of the Amorphous: Bill Viola's Videoscapes, Poetry on & Off the Page: Essays for Emergent Occasions, by Northwestern University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8101-1561-1

- ^ "Video art by pioneer Bill Viola comes to RAMM". RAMM. December 15, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Reverse Television -- Portraits of Viewers (Compilation Tape)". Electronic Arts Intermix. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "The Quintet of Remembrance". MOMA.org. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ Alan Rifkin: Bill Viola, Los Angeles Times, January 28, 2007

- ^ Carroll, Jane (2019). "Connecting with the Unseen World". Beshara Magazine. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ "Bill Viola: Venice Biennale 2007". Tate.org.uk. July 29, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Rose, Cameron (2014). Poetic documentary and visual anthropology: representing intellectual disability on screen (PhD). Monash University.

Bill Viola's homage to 9/11 Observance (2002) successfully demonstrates the affective power of the moving image.

- ^ Adrian Searle: Bill Viola: Haunch of Venison/St Olave's College, London, The Guardian, June 29, 2006

- ^ a b "'Tristan Project': For Epic Wagner, Just Add Video". NPR.org. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "Welcome". The Night Journey.

- ^ "Welcome". The Night Journey.

- ^ "Browse by Events :: Past Selections :: IndieCade - International Festival of Independent Games". www.indiecade.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Baker, Tamzin. "Bill Viola." Modern Painters, November 2009.

- ^ "BILL VIOLA. THE INVISIBLE HOURS". caac.es. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ Wardrip-Fruin, Noah & Montfort, Nick (2003). The New Media Reader. The MIT Press.

- ^ a b c Viola, Bill. "Will There Be Condominiums in Data Space". The New Media Reader. The MIT Press.

- ^ New Media Reader: Jorge Luis Borges' "The Garden of Forking Paths"

- ^ "22nd Premi Internacional Catalunya 2010" Archived May 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bill Viola". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "3 Visual Artists Win $5,000 Film Awards". The New York Times. February 1, 1988.

- ^ "Bill Viola biography". EAI.org. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "Mr. Bill Viola". amacad,org. July 2, 2024. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "Video artist Bill Viola to receive McDermott award". February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Université de Liège - Bill Viola reçoit les insignes de docteur honoris causa". Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Praemium Imperiale Art Awards 2011 Ceremony". Archdaily.com. November 5, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

Further reading[edit]

- Viola, Bill, Peter Sellars, John Walsh, and Hans Belting. Bill Viola: The Passions. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum in association with the National Gallery, London, 2003. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50868268

- Hanhardt, John G, Kira Perov, and Bill Viola. Bill Viola., 2015. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/907140211

- Townsend, Chris, and Bill Viola. The Art of Bill Viola. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/55917902

- Viola, Bill, and Jérôme Neutres. Bill Viola: Paris, Grand Palais, Galeries Nationales, 5 Mars-21 Juillet 2014., 2014. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/876749116

- Viola, Bill. Going Forth by Day. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2002. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/51451889

- Viola, Bill, and Robert Violette. Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House: Writings 1973-1994. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1995. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32274380

- Rogers, Holly. 'Acoustic Architecture: Music and Space in the Video Installations of Bill Viola'. Twentieth Century Music, (2005) 2(2), pp. 197–219. ISSN 1478-5722

- Ross, David A, Peter Sellars, and Lewis Hyde. Bill Viola. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/37239009

- Hanhardt, John G, Thomas A. Carlson, and Kira Perov. I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like. Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2019. Print. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1055265333

External links[edit]

- Bill Viola at IMDb

- Bill Viola discography at Discogs

- Cameras are Keepers of the Souls. An interview with Bill Viola Video by Louisiana Channel